?The REAL Start-Up Nation – What Makes Israelis Inventive

Presentation by Shlomo Maital * to the inaugural meeting of the Israeli Semiconductor Club

Tel Aviv, Sept. 20/2010

?The REAL Start-Up Nation – What Makes Israelis Inventive

Presentation by Shlomo Maital * to the inaugural meeting of the Israeli Semiconductor Club

Tel Aviv, Sept. 20/2010

A recent BBC World Service poll completed in February reveals a painful fact − Israel is regarded by much of the world as illegitimate, a pariah, a social reject. The survey covered 29,000 people, interviewed by phone or face-to-face in 28 countries. The question was: For each of 17 countries, do you regard the influence of Country X in the world as mostly positive or mostly negative?

Half the respondents rated Israel's influence as negative. Only 19 per cent rated it as positive. The rest were either neutral or 'don't know'.

Incredibly, the results for North Korea are slightly better than for Israel; Iran rates only slightly worse. In only two of 28 countries does Israel have a perceived net positive balance: America and Kenya. And in America, only 40 per cent gave Israel a "positive" rating, down from 47 per cent a year ago. There is not a shred of evidence that Israel's leaders lose sleep over these terrible numbers, let alone take action.

Against this tsunami of anti-Israel sentiment, rises Start-up Nation, the best-selling book about Israeli innovativeness by Dan Senor and Saul Singer. This best-selling book has aroused enormous interest in the source of Israel's boundless creativity, mainly in the U.S. but in other countries as well. Thousands are reading the book to learn how Israel invented the cell phone, Copaxone, Azilect, a kind of heart pump, drip irrigation, the Given Imaging pill that 'broadcasts' your intestines' condition, the Pentium and Centrino chips, drip irrigation, cherry tomatoes, and a thousand other life-changing inventions, while fending off enemies and squabbling endlessly with one another. Former NBC TV anchor Tom Brokaw wrote, "There is a great deal for America to learn from the very impressive Israeli entrepreneurial model… START-UP NATION is a playbook for every CEO who wants to develop the next generation of corporate leaders."

"What is driving (Israeli inventiveness)," Senor recently told the cable network CNBC, "is a national ethos, resilience, the fight for survival." The book itself stresses two qualities embedded in Israeli culture: Hutzpah (brash impudence, willingness to challenge anything) and leadership experience gained in the Israeli Army.

Start-Up Nation’s stories about Israeli entrepreneurs are truly wonderful. But can we dig deeper beneath these stories and find empirical research that illuminates this phenomenon?

Are the Stories About Israeli Innovation Just Myths? Israel’s foes may argue that ‘stories’ prove nothing, and that despite the enormous number of inventions attributable to Israelis, perhaps Israeli innovation is simply a myth. An examination of data compiled by IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook project (2010) proves otherwise. According to these data, Israel is tops, or among the top 3 nations, in 14 variables closely related to innovation:agricultural productivity, skilled labor availability, finance skills, availability of venture capital, funding for technological development, flexibility and adaptability, technological cooperation among companies, public and private ventures that support technological development, R&D as % of GDP, business R&D as % of GDP, scientific research knowledge, transfer between companies & universities, IT skills, and qualified engineers

Start-Up Nation is no myth.

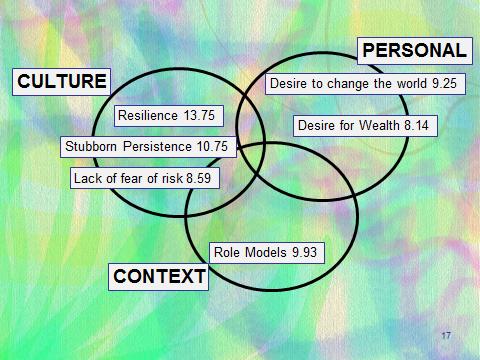

Ask the innovators: With the aid of Shlomo Gradman, founder of the Israeli Semiconductor Club, we asked those who registered for the inaugural event to answer a brief questionnaire eliciting their opinion on the relative importance of some 13 innovation factors. (See Box). We received nearly 50 responses, out of 200 registered participants. They came from a slice of Israeli high-tech industry engaged in innovative chip design. A summary of the responses is shown in Table 1 and in Figure 1 below.

Questionnaire: Start-Up Nation

What in your view are the main factors that drive Israeli innovativeness ? You have 100 “shekels” to invest. Allocate them according to what you believe is the importance of each of the following elements. Your ‘investments’ should add up to 100:

CULTURE

___ Hutzpah

___ Stubborn persistence

___ Resilience (overcoming hard times)

___ Lack of fear of risk

___ Willingness to break rules

___ Willingness to challenge authority

CONTEXT

___ Role models (successful entrepreneurs)

___ Army leadership experience

___ Army technology experience

PERSONAL

___ Desire for wealth

___ Desire for fame

___ Desire for independence (not be told what to do)

___ Desire to change the world

OTHER: _________________________________

100 = TOTAL:

————————————————————————————————————————

Table 1. 13 Innovation Factors, by Rank and Mean Score.

RANK FACTOR MEAN

1 Resilience 13.75

2 Stubborn Persistence 10.75

3 Role models 9.93

4 Desire to change the world 9.25

5 Lack of fear of risk 8.59

6 Desire for wealth 8.14

7 Willingness to break rules 6.7

8 Desire for independence 6.23

9 Willingness to challenge authority 5.45

10 Hutzpah 5.16

11 Army technology experience 4.93

12 Army leadership experience 4.32

13 Desire for fame 2.48

Figure 1. Top Six Innovativeness Factors: Culture (3), Personal (2), Context (1)

Three of the top five innovativeness factors are “cultural” in nature, deriving from Israeli culture: Resilience, stubborn persistence and lack of fear of risk. One is contextual (role models – other Israeli entrepreneurs who have done great things), and one is ‘personal’ but with a strong cultural element (desire to change the world). It is interesting that army experience in both technology and leadership, cited as strong factors by Start-Up Nation, ranked 11th and 12th out of 13. This may in part reflect that respondents are chip designers, a technology not central to IDF R&D efforts.

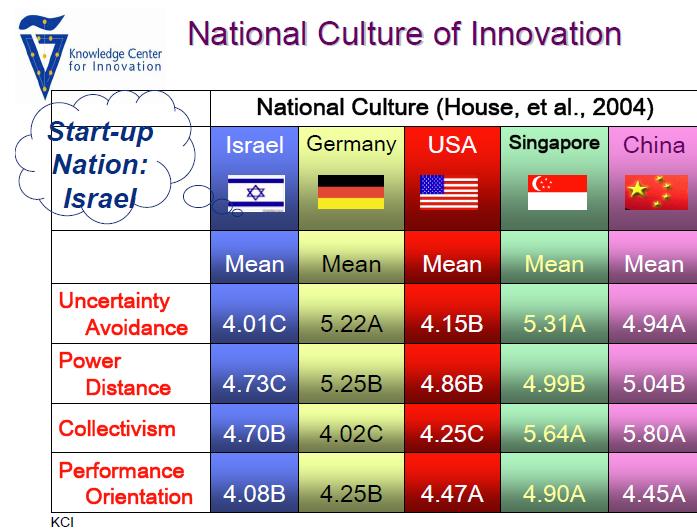

Cultural Factors: Technion Prof. Miriam Erez, an organizational psychologist, participated in a global study led by Robert House, in which several quantifiable dimensions of culture were measured and compared across several countries. Israel proved to be an outlier in several of those dimensions. (See Table 2).

Table 2. Israeli Cultural Dimensions of Innovation

● Uncertainty avoidance: Israel, it is said, lives in a rather unstable ‘neighborhood’. This makes Israelis accustomed to living with uncertainty. When they encounter such uncertainty in innovation efforts, they are not deterred. Table 2 shows Israel scores lower on this dimension than Singapore (very high), Germany (also high), China and even the U.S.

● Power distance: This measures the degree to which individuals perceive the ‘distance’ (in authority, or power) between themselves and those to whom they report, or who lead, to be very great. It is a measure pioneered by Gerd Hofstede. Israelis score exceedingly low in power distance. Note that this is despite the fact that most Israelis serve as youths in a highly hierarchical organization, the Army. Here is an anecdote that illustrates this cultural quality, which may in part be related to “hutzpah”, or brashness, as related by the Start-Up Nation authors:

Paypal acquired an Israeli startup named FraudSciences. President Scott Thompson went to Tel Aviv to meet with the FraudSciences team. He told us about his first meeting with the staff: Every question was penetrating. I actually started to get nervous up there. I’d never before heard so many unconventional observations — one after the other. Junior employees had no inhibition about challenging how we had been doing things for years. I’d never seen this kind of completely unvarnished, unintimidated, and undistracted attitude. I found myself thinking, “who works for whom here? Did we just buy FraudSciences, or did they buy us?”

●Performance Orientation: There is, however, a dark side to Israeli inventiveness. Intel Executive VP David Perlmutter and former Intel senior development engineer Avinoam Kolodny have pointed out that as inventions proceed to market launch, the ‘eutectic’ point (optimal combination, drawn from the science of metallurgy and alloys) showing optimal combinations of chaotic creativity and orderly discipline, changes toward discipline. Israelis score low on performance orientation, lower than US, China, Singapore for certain, and Germany. This is the dark side of creativity – the need for orderly, disciplined processes that bring inventions to market and that manage projects on time and on budget. Perhaps this is one reason Israel has generated thousands of startups but the last one to reach significant global scale was established in 1995.

Case study: We began by asking whether there are data that can reinforce the many Start-Up Nation stories. We end by adding a story of our own, one that we believe captures most of the essential elements of the Real Start-Up Nation: Holocaust, Army, hutzpah, collaboration, etc.

Kibbutz Lehavot HaBashan (‘the Flames of Bashan’) is located 10 kms. (6 miles) south of Kiryat Shmoneh, nestled below the Golan Heights just west of the Jordan River. It was started by a group of pioneers who came together in 1945 to launch a new kibbutz and settled on the present site in 1947. Over 40 years ago, the kibbutz sought to diversify its agricultural revenue by starting a factory. They decided to make fire extinguishers, perhaps inspired by the kibbutz’s name. For years, red Lehavot extinguishers had a near-monopoly in the closed Israeli market and the plant thrived. But in the 1990’s, import tariffs were sharply cut and cheap imported extinguishers flooded in. The factory drowned in red ink, as losses mounted. Key managers left. Credit dried up, as banks stopped lending. Lehavot’s prospects were dismal and its workers were demoralized.

In August 2005, Aharon Shita showed up. A graduate of Ben Gurion University in electrical engineering, he served in the career army (Signal Corps lieutenant colonel), then became a senior executive at Bezeq phone company, Nortel and Clal Technologies. He was asked to become CEO of Lehavot (later known as LVT), and he agreed, partly because one of his children had moved to the North.

What Shita found at Lehavot was a grubby building with walls black with soot. But where others saw only gloom, he saw promise. “The workers who remained had been through hard times and were very resilient,” he said. “And there were tiny sparks of creativity, ideas that had been suggested but dropped.”

The first thing he did was to buy paint and paint brushes. He and the workers painted the place white. It was a signal that major change was about to take place. Then, after whitewashing the past, he tackled the future.

“Without vision,” the prophet Isaiah said, “the nation disintegrates”. CEO Shita created a vision to drive Lehavot forward. He intuitively understood what management guru Jim Collins, author of Good to Best, calls BHAG’s – Big Hairy Audacious Goals. Our vision, Shita decided, is to become “a leading producer at the cutting edge of technology”.

Say again? An old decrepit plant on a remote kibbutz, without money, management or technology, far from export markets? The “cutting edge of technology”? Hutzpah! Fantasy! Collins says a strong vision should arouse laughter. I am certain Shita’s vision did. But he convinced his Board of Directors to support him.

Next he shut down a business that was unprofitable – refurbishing old fire extinguishers for the Israeli Army. This involved a few layoffs, not easy for a left-wing kibbutz to accept (its members, essentially, were Shita’s Board of Directors). Shita understood that in order to create new things, you have to shut down old ones. But the really tough part lay ahead.

He made the obligatory pilgrimage to the banks in Tel Aviv to borrow money. They threw him out.

But slowly, things began to turn around. In 2006 Lehavot developed a system for putting out fires in cell phone antennas, vulnerable to vandalism. Cash flow turned positive. However, the Israeli market was limited. Shita and his team decided they had to aim for exports to foreign markets.

Shita’s idea team was led by Ilan Elhalal, veteran kibbutz member and a worker at the Lehavot plant since the 1980’s. Elhalal assembled a handful of talented engineers, many of them veterans of elite commando units. The team developed a revolutionary new product known as Zone 5 – rapid automatic fire suppression in wheeled armored vehicles of the kind used by U.S. Infantry and Marines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Loaded with gasoline and ammunition, these vehicles are vulnerable to fire, easily started by rifle-propelled grenades, improvised explosive devices or even light arms fire. Why Zone 5? Because the system, unlike that of competitors, doused fires in all five sensitive points of military vehicles, including the rubber tires (devilishly hard to extinguish), engine, and interior. Shita knew instinctively that only a comprehensive fire-suppression system would be competitive.

Lehavot’s neighbor is Kibbutz Sasa, home of Plasan, world leader in ballistic armor for military vehicles. Plasan’s CEO Dani Ziv asked Shita if he could supply on very short notice Zone 5 fire suppression systems for Plasan demonstration vehicles to be sent to the crucial upcoming Army-USA trade fair exhibition in Washington, D.C. Shita’s team pulled together, worked day and night and made the deadline.

Zone 5 was a huge hit. Orders poured in. And that led to a major crisis.

Lehavot’s Zone 5 innovation was based on a unique fire-detection sensor developed by a genius inventor named Eli Hatzir, whose Ashdod-based startup company Firesys had been acquired by Lehavot. Hatzir assembled the sensors by himself at a rate of one per month. But the US Army wanted 16 of them for testing within two months! The stress overwhelmed Hatzir. Shita sent one of his best managers to learn from Hatzir how to make the complex sensors and then he produced 16 of them, on time, within two months. (“Yes, we can” was not invented by Barack Obama.)

Aharon’s father lived through the Holocaust as a teenager, coming to Israel at age 18. Aharon himself was born when his father was only 20 years old, not long after his father’s wrenching Shoah ordeal, recounted to him in full. He recounted that his father’s Shoah experience has powerfully influenced his life. “No matter how tough things were for me,” he said, “I always told myself, look, this is nothing compared to what my father went through”.

What does the future hold? LVT continues to come up with pioneering inventions. For example, take the one developed by R&D engineer Carlos Feller, who came to Israel as a youth from Argentina. The US Army wanted LVT’s fire extinguishers to be hardened, encased in armor, so they would not explode and wound soldiers if hit by shrapnel or a bullet. Such ‘armor’ adds unacceptable weight and cost.

Carlos found a solution. He once observed soldiers wearing ceramic flak jackets. “Okay,” he said, “let’s put little flak jackets on our extinguishers.” This idea, now patented, is light, effective, cheap and is another winning product for LVT. It is the kind of innovations Israelis are good at. Slipping flak jackets on fire extinguishers is truly out-of-the-box thinking.

Innovation Eco-system: Every entrepreneur knows there is an element of good fortune, or luck, in every startup. Start-Up Nation is no exception. Just as the global economy took off, with the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989, Israel got a windfall of a million highly educated persons from the former Soviet Union, between 1990 and 2000. This proved to be a key part of Israel’s innovation eco-system, along with, for instance, the burgeoning venture capital industry. It recalls the rapid growth of Dell Computer Co. during 1992-2000, which hired many thousands of experienced engineers who were fired or laid off by IBM. Had it not been for IBM’s firings, Dell would not have been able to engage in massive hirings.

Peter Drucker used to teach a successful course at NYU known as “Innovation and Abandonment”, stressing that often “abandonment” (closing unsuccessful businesses) is vital before new innovative businesses can be launched. Had it not been for ‘abandonment’ at IBM, Dell’s innovation could not have taken off. Had not the USSR been disbanded, and Russian Jews emigrated to Israel, Israeli innovators would have lacked the engineers to staff its startups.

When a key part of any ecosystem fails, the whole system fails. Today, Israel’s innovation ecosystem faces serious challenges. Two-thirds of high-tech exports are bought by the US and EU, markets which are struggling to recover from global crisis. Venture capital funds have fallen precipitously. There is a overt shortage of skilled engineers. Global companies are shifting their R&D operations from Israel to Asia.

When these challenges were presented to the Semiconductor Club audience, one participant raised his hand and said simply: We are resilient. We will overcome.

* senior research fellow, S. Nea